A Fokker-Planck integrator in python

Project description

Fokker-Planck: A Dynamic Integrator for Python

Installation

To install this package through pip use:

pip install fokker-planck

Table of Contents

- Overview

- The Fokker Planck Equation

- A Preview

- 1D Simulations

- 2D Simulations

- The Simulator Interface

- In the Weeds: Integrator Options

- Additional Resources

- References

Overview

The intent of this package is to provide simple and user-friendly access to a Fokker-Planck equation integration suite that makes is relatively quick and simple for the end-user to run simulations of stockastic systems within a dynamic potential energy function, as well as trcking and investigating the steady state and time-dpendent properties of physical observables and quantities of interst, like work, power, and flux.

This is made possible by abstracting away many of the low-level detaisl of the integrator itself, and focusing on providing a simple interface that allows users to rapidly build pupose-built simulations, and allows for the flexibility of the system to be generalizable, extensible, and modular enough to be improved upon easily.

At its heart, this package is interested in integrating/solving the Fokker-Planck equation

In this README we first discuss the basics of the Fokker-Planck equation as it is often used, and then move onto the base case of a 1D integration, then briefly discuss the 2-dimensional extension. Following this, we introduce the Simulator interface, and show how its possible to run several nontrivial simulations of physical system behaviour through its use, and the necessary requirements to customize that behaviour for specific purpose-driven investigations.

Fokker Planck equation

Simply put, this software package deals with the Fokker-Planck equation. This equation represents the time-evolution of a probability distribution over states for a system that evolves under drift and diffusion. In fact, one can derive the FPE from the effective 'continuity' equation for stochastic processes,the Chapman Kolmogorov equation (see Chapter 3 of Ref.[2]). This means that the resulting behaviour is diffusive in nature, and will not capture heavy-tailed distributions or situations where anomalous diffusion takes place. For that, we would need to model a jump kernel explicitly into the equation, or support fractional derivative terms, which we do not.

However, in full generality the FPE representing this type of evolution can be represented in $N$-spatial dimensions as

$$ \partial_t p(\boldsymbol{x}, t) = \sum_i \partial_{{x_i}} \left[\mu(\boldsymbol{x}, t) p(x, t)\right] + \sum_{i, j}\partial_{x_i, x_j}^2D_{ij}p(\boldsymbol{x}, t) $$

which is rather complicated, but essentially allows for arbitrary mobilities $\mu$ as a function of the state vector $\boldsymbol{x}$. For the initial release of this package we support a somewhat simplified, single-dimensional, version of this equation known as the Smoluchowski Equation that represents the stochastic dynamics of an overdamped particle under the influence of potential energy function $U(x, \boldsymbol{\lambda})$, where $\boldsymbol{\lambda}$ (not commonly used in the definition of the Smoluchowski equation) represents a control parameter vector, which parameterizes time-dependence of the potential energy function (something we will see in depth soon). Mathematically, this equation is

$$ \partial_t p(x, t) = -\beta\partial_x \left[ U'(x, \boldsymbol{\lambda})p(x, t) \right] + D\partial^2_{xx}p(x, t) $$

where $U'(x,\boldsymbol{\lambda})$ is the position-dependent force experienced by a particle at location $x$. Ultimately, the current functionality of this package serves to numerically integrate this equation in a way that provides accurate time-dependent tracking of the probability distribution through time. As we will show this allows a number of nontrivial quantitative calcualtions to be made for model systems of interest.

A Preview

Before delving into more detail on the individual components and their uses, we breifly show in this section how to run a simple simulation of a diffusing particle in a 1D harmonic trapping potential, through the use of the Simulator interface.

The code snippet below shows how simple such a procedure is, starting with a system initialized from a Gaussian distribution an iterating the dynamics for 1000 steps (total_time / dt)

from fokker_planck.simulator import simulator

import fokker_planck.forceFunctions as ff

# Define the model configurations

fpe_config = {

"D": 1.0, # Diffusion coefficient

"dx": 0.01, # Discretization in x-dimension

"dt": 0.00025, # Time discretization

"x_min": -2, # minimum x-value in domain

"x_max": 1 # maximum x-value in domain

}

# Harmonic trap strength

trap_stringth = 16

# initial distribution parameters

init_var = 1 / trap_strength

init_pos = -1

# Total time of simulation

total_time = 0.25

# Initialize simulator object, passing the configuration parameters for the

# integrator, as well as the trap parameters

fpe_sim = simulator.HarmonicEquilibrationSimulator(fpe_config, trap_strength)

# Initialize the probability, this could also be done in the constructor of

# the simulator object, in this case it will initialize to a Gaussian

# distribution

fpe_sim.initialize_probability(mean=init_pos, init_var=init_var)

# run the simulation!

sim_result = fpe_sim.run_simulation(total_time)

The result type will be SimulationResult (or some custom subclass of that type) and will contain all of the desired information on the simulation run. Also, this type can obviously be subclassed and expanded to contain any desired information. For instance, in slightly more complex scenario, we can define our own energy and force functions, to simulate the behaviour of whatever systemwe want to simulate.

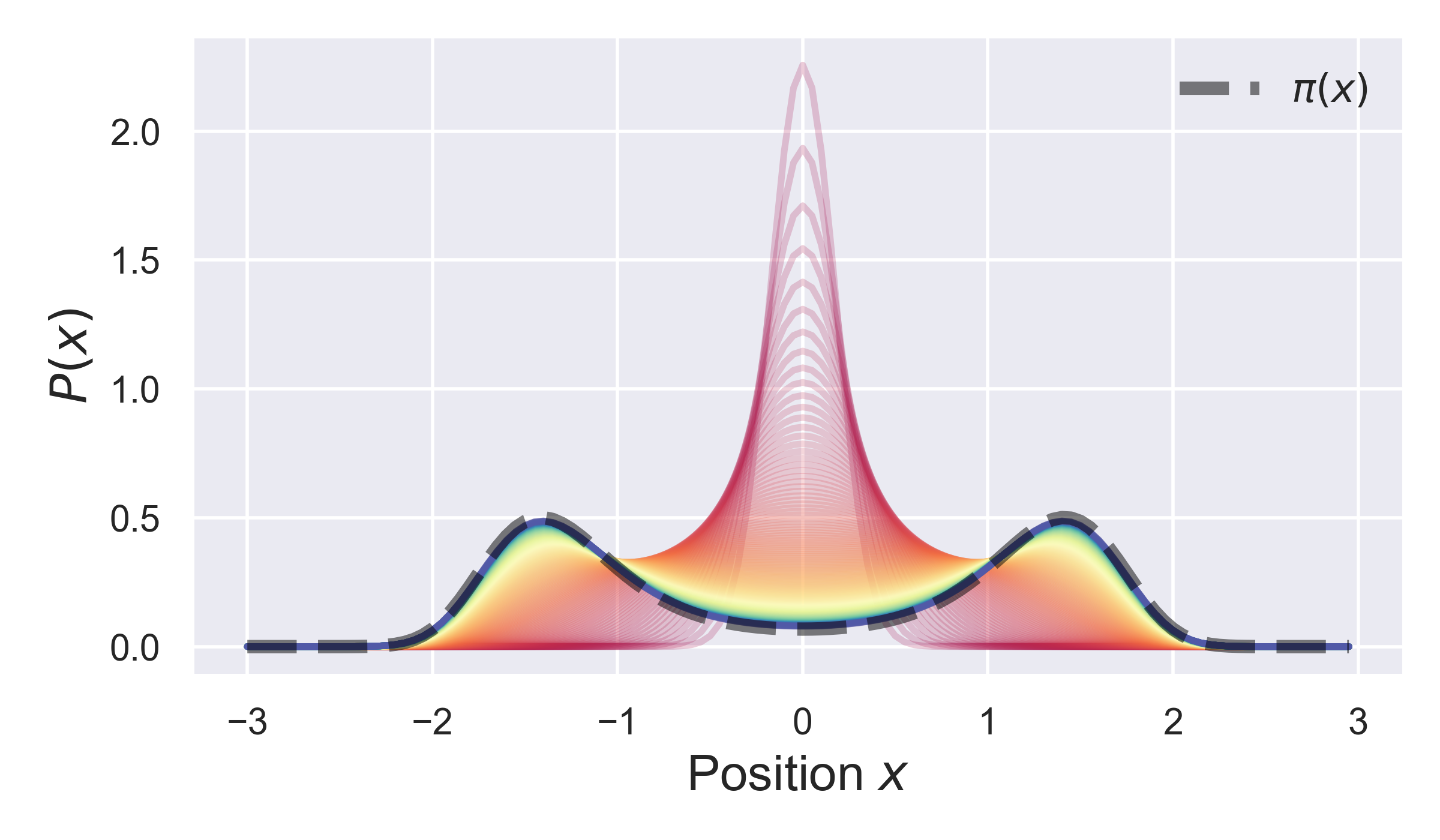

For this specific scenario, the static simulator will populate an array of probability distributions (called prob_tracker that will be present on all SimulationResult objects) through time, at intervals of a specficied number of timesteps, as a means of tracking the evolution of the initial distribution. As a result, we can visualize the evolution of the system over time:

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import seaborn as sns

sns.set(style='darkgrid')

Pal = sns.color_palette('Spectral', len(sim_result.prob_tracker))

fig, ax = plt.subplots(1, 1, figsize=(6, 3.5))

for i, prob in enumerate(sim_result.prob_tracker):

ax.plot(sim_result.x_array, prob, color=Pal[i], alpha=0.6)

The results of this plot are shown below.

Here, we can see the initial distribution converges towards the equilibrium distribution (black dashed line) over time.

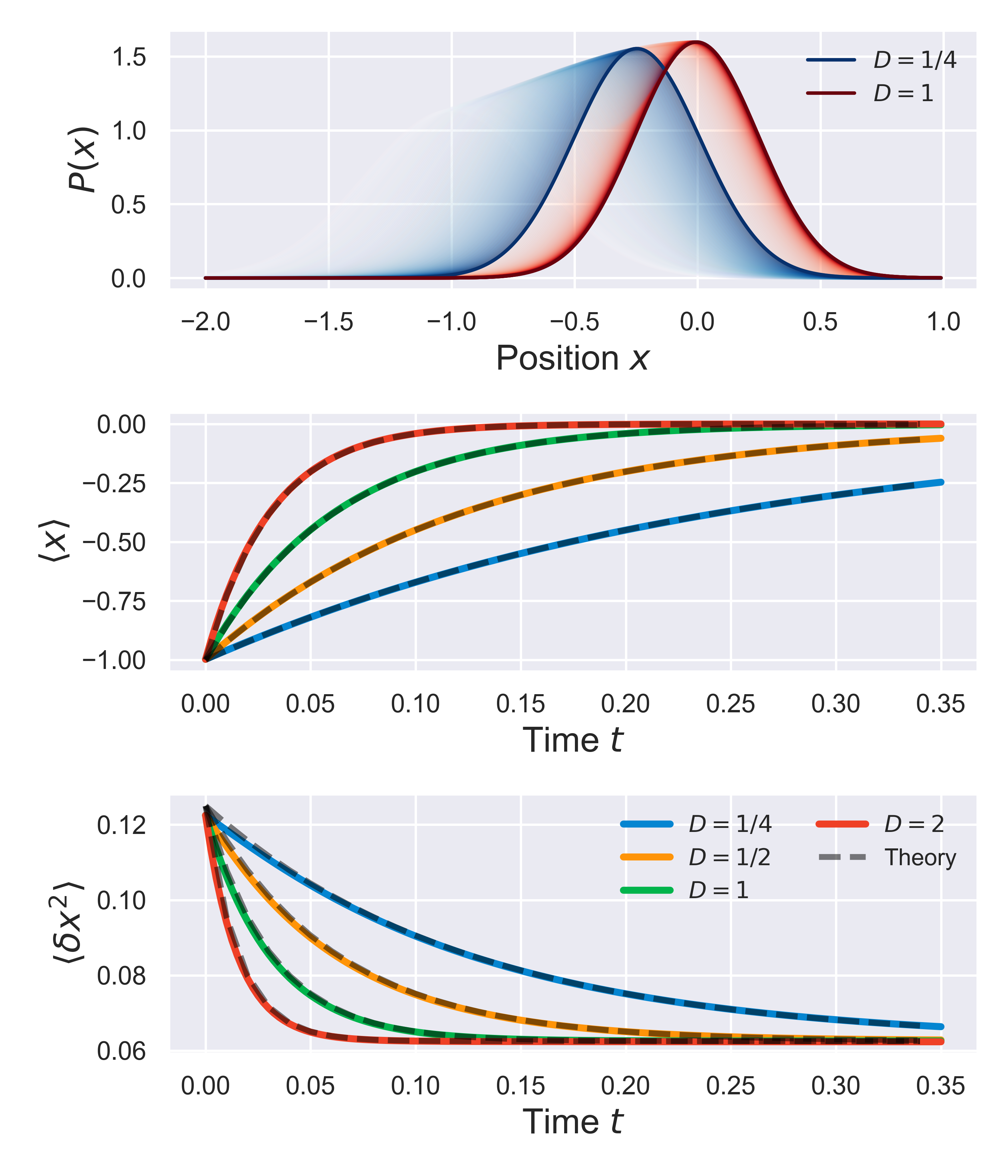

In fact, we can be even more quantitative about this. Following the procedure for this testing outlined in notebook notebooks/functionality.04-slarge-advection-diffusion.ipynb, we can also track the distribution variance and average position over time, and compare them to known analytical results. Specifically, for a stochastic system in a parabolic potential with trap strength $k_{\rm init}$, that is initially in a Gaussian distribution with mean position $\langle x\rangle = a$ and variance $\sigma_{\rm init}$, the time-dependent variance and mean should evolve according to

$$ \langle x(t) \rangle = $$ $$ \langle\delta x^2(t)\rangle = $$

The figure below shows the time evolution of these values in time, for a few sample trap strengths, as compared to the theoretical results (black dashed lines). This shows that not only the qualitative features of the tiem-evolution are consistent with theory, but also that the quantitative evolution is as expected.

1D Simulations

As of this point, 1D simulations are all that are supported by the integrator. Full details on the integration process are outlined in supporting documentation, but we outline here the basic ideas behind the integration scheme.

Put broadly, there are 3 key pieces to the construction of the integrator:

- the advective term

- the diffusive term

- the operator splitting methodology that stitches them together. The advection term (the one that corresponds to the forcing term) uses a second-order accurate in time method known as the 2-step Lax-Wendroff method, while the diffusion term is updated using the Crank-Nicolson method (which is also second order in time). Now, we able to do these two updates separately because of the operator splitting methods adopted in updating the full probability. Put simply, we can separately apply updates from the advective and diffusive components of the motion, in such a way that replicates (up to a certain accuracy) the simultaneous application of the entire equation.

The details of these methds, and independent tests of their efficacy are contained in a series of notebooks in the github source under the locations:

notebooks/functionality/01-slarge-advection.ipynb: Advection termnotebooks/functionality/02-slarge-diffusion.ipynb: Diffusion termnotebooks/functionality/03-slarge-operator-pslitting.ipynb: Operator splitting methods

Once this is put together, one can simulate dynamics of a system governed by the Smoluchowski equation, for an arbitrary potential energy function (given that the parameter satisfy the appropriate stability conditions).

To see how this can be used to model the energetic inputs for model physical systems such as a constant-velocity harmonic trap, or a harmonic potential with a time-dependent spring constant, as well as in the physics of a system evolving within a sinusoudal potential, see the notebooks:

notebooks/functionality/advection-diffusion.ipynb: Constant-velocity trap, and other thingsnotebooks/functionality/breathing-trap.ipynb: Time-dependent spring constantnotebooks/functionality/periodic-system.ipynb: Periodic system

2D Simulations

Not yet implemented: This is a feature that is coming down the pipline soon!

The Simulator Interface

Ultimately, the ease-of-use of the package is made possible through the Simulator interface. The goal of this, is to create an abstraction of the core integrator functionality, so the end-user can access a simple and customizable interface that makes the process of solving and exploring problems of interest a simple task.

The simulator interface is defined in the base class simulator/base.py, which defines the low level functionality. At present, there are two abstract subclasses of this base class: DynamicSimulator and StaticSimulator, which repspectively, provide common functionality for simulations that are meant to track behaviour within a dynamic or static potential.

On initial release, there are two static Simulators implemented, and two dynamic simulators (the periodic system has not as of yet been converted into a simulator class).

Static Simualtors

To define a static simulator object, you just need to define instance variables force_func and force_params, or pass them into the parent constuctor, as well as provde a probability initialization routine. So long as this is done. For example, below shows a simplified implementation of the HarmonicEquilibrationSimulator class (which is located in fokker_planck/simulator/simulator.py in the source code)

from fokker_planck.simulator.base import StaticSimulator1D

import fokker_planck.forceFunctions as ff

class HarmonicEquilibrationSimulator(StaticSimulator1D):

def __init__(self, fpe_config: dict, k_trap: float, trap_min: float = 0.0):

super().__init__(fpe_config)

self.force_func = ff.harmonic_force

self.force_params = [k_trap, trap_min]

def initialize_probability(self, init_var: float):

# Pass the trap minimum along with the inital variance to the

# in-build Gaussian probability initialization routine

self.fpe.initialize_probability(self.force_params[1], init_var)

ow, from this, we can relatively simply run a simulation that shows a system relaxing into an equilibrium with the harmonic potential by similar means as the first code cell:

from fokker_planck.simulator import simulator

import fokker_planck.forceFunctions as ff

# Define the model configurations

fpe_config = {

"D": 1.0, # Diffusion coefficient

"dx": 0.01, # Discretization in x-dimension

"dt": 0.00025, # Time discretization

"x_min": -2, # minimum x-value in domain

"x_max": 2 # maximum x-value in domain

}

# Harmonic trap strength

trap_stringth = 8.0

# Total time of simulation

total_time = 0.25

# Initialize simulator object, passing the configuration parameters for the

# integrator, as well as the trap parameters

fpe_sim = simulator.HarmonicEquilibrationSimulator(fpe_config, trap_strength)

# Initialize the probability, this could also be done in the constructor of

# the simulator object, in this case it will initialize to a Gaussian

# distribution, shiftd off of the equilibrium position by 0.25

fpe_sim.initialize_probability(mean=-0.25, init_var=1/16)

# run the simulation!

sim_result = fpe_sim.run_simulation(total_time)

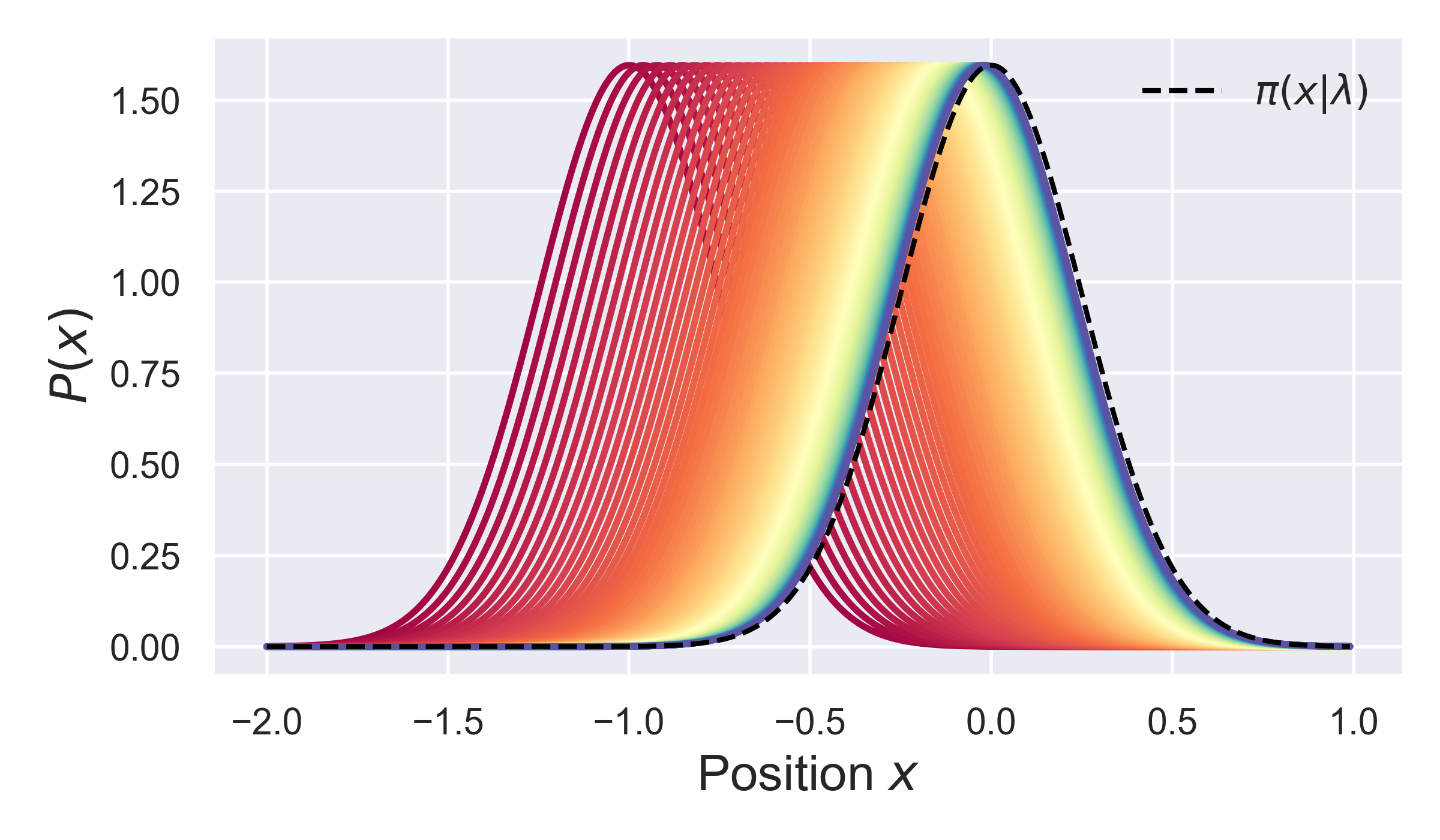

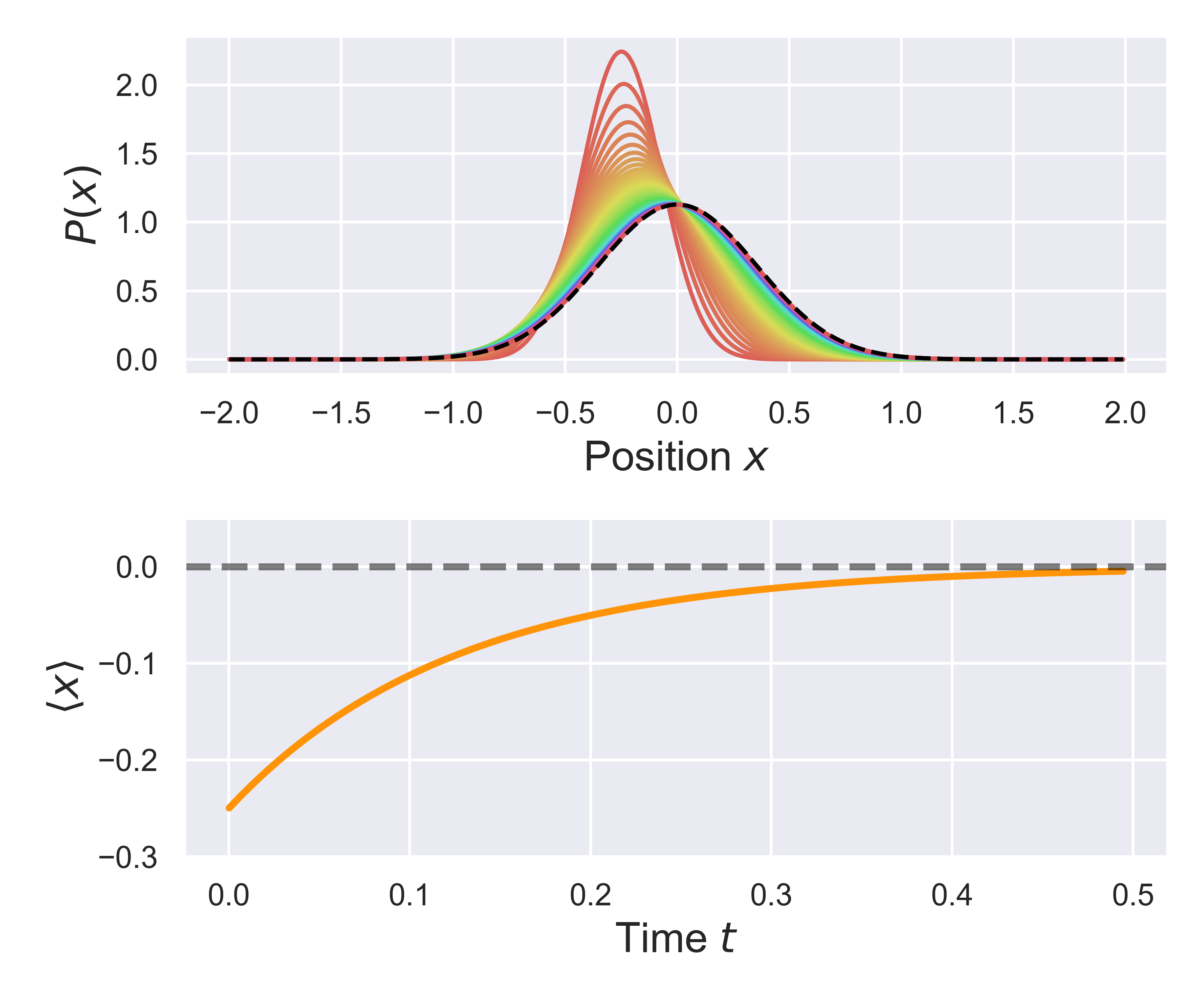

Based on the result of this simulation, we can plot the evolution of the probabiity over time, as well as the time-dependent position of the distribution mean. The figure below shows bowth of these things, and compares the distribution to its asymptotic (equilibrium) dstribution, as shown by the black dashed line.

Curretly, there are 2 static simulators defined, one for equilibration within a harmonic potential, and one defined for equilibration/relaxation in a periodic (sinusoidal) potential. However, to create a new static simulator, for a different potential, you just need to deine an appropriate orce function, and then create a class which implements the methods above, and the simulation should work.

For instance the code below would create an equilibration simulator for a force that follows the combination of a sin and cosine potential, phase shifted from one another.

def sample_force_func(x, params):

return np.sin(x) + np.cos(2*np.pi*x + params[0])

class ExampleEquilibrationSimulator(StaticSimulator1D):

def __init__(self, fpe_config: dict, phase_shift: float)

super().__init__(fpe_config)

self.force_func = sample_force_func

self.force_params = [phase_shift]

def initialize_probability(self, init_var: float):

# Pass the trap minimum along with the inital variance to the

# in-build Gaussian probability initialization routine

self.fpe.initialize_probability(self.force_params[1], init_var)

Which should work, given the configuration has parameters that are stable.

Dynamic Simulators

The dynamic simulators provide additional fucntionality beyond what exists for the static scenarios. For the dynamic simulators, you are required to implement 3 methods:

initialize_probability(...): code to initialize the prbability distributionupdate(...): A method to update the probability distrubiton, typically by calling theself.fpe.integrate_steporself.fpe_work_steproutines, deending on if you want to track energy flows or not.build_friction_array(...)Optional, but if you want to study optimal protocols, than this method is requred, and simply requires that for the input array of contraol parameter values, we can associate a value representing the generalized friction tensor.

In practice, using the dynamics simulators requires slightly more specification, but it is not too burdensome, considering the somplexity of wwhat is happening behind the scenes. For instance, the code for implementing the Breathing trap simulator (a time dependent spring constant) is shown below,

class BreathingSimulator(DynamicSimulator1D):

def __init__(

self, fpe_config: dict, k_init: float, k_final: float,

force_function, energy_function

):

super().__init__(fpe_config, k_init, k_final)

self.force_func = force_function

self.energy_func = energy_function

def build_friction_array(self):

return self.lambda_array ** (3/2)

def initialize_probability(self):

self.fpe.initialize_probability(0, 1/self.lambda_init)

def update(self, protocol_bkw, protocol_fwd):

# Second parameter is the trap minimum value

params_bkw = ([protocol_bkw, 0])

params_fwd = ([protocol_fwd, 0])

if not self.check_cfl(params_fwd, self.force_func):

raise ValueError('CFL violated')

self.fpe.work_step(

params_bkw, params_fwd, self.force_func, self.energy_func

)

The SimulationResult

References

- "Thermodynamic Metrics and Optimal Paths", D.A. Sivak & G.E. Crooks, Phys. Rev. Lett., 2012

- "Optimal Control of Rotary Motors"

- "Stochastic Control in Microscopic Nonequilibrium Systems"

Project details

Release history Release notifications | RSS feed

Download files

Download the file for your platform. If you're not sure which to choose, learn more about installing packages.

Source Distribution

Built Distribution

Hashes for fokker_planck-1.0.12-py3-none-any.whl

| Algorithm | Hash digest | |

|---|---|---|

| SHA256 | 6af0087bcb31db1a3df0f1fddbc9db4019c9f401d3a832b22cf176998851ce58 |

|

| MD5 | 080be1a3177a85a538dc943762d29003 |

|

| BLAKE2b-256 | 802d04e394089c68190b76985f0f2ad800fbaf0f993997a96aab2360269faa49 |